What is Tibetan Medicine?

“The Science of Health and Happiness”

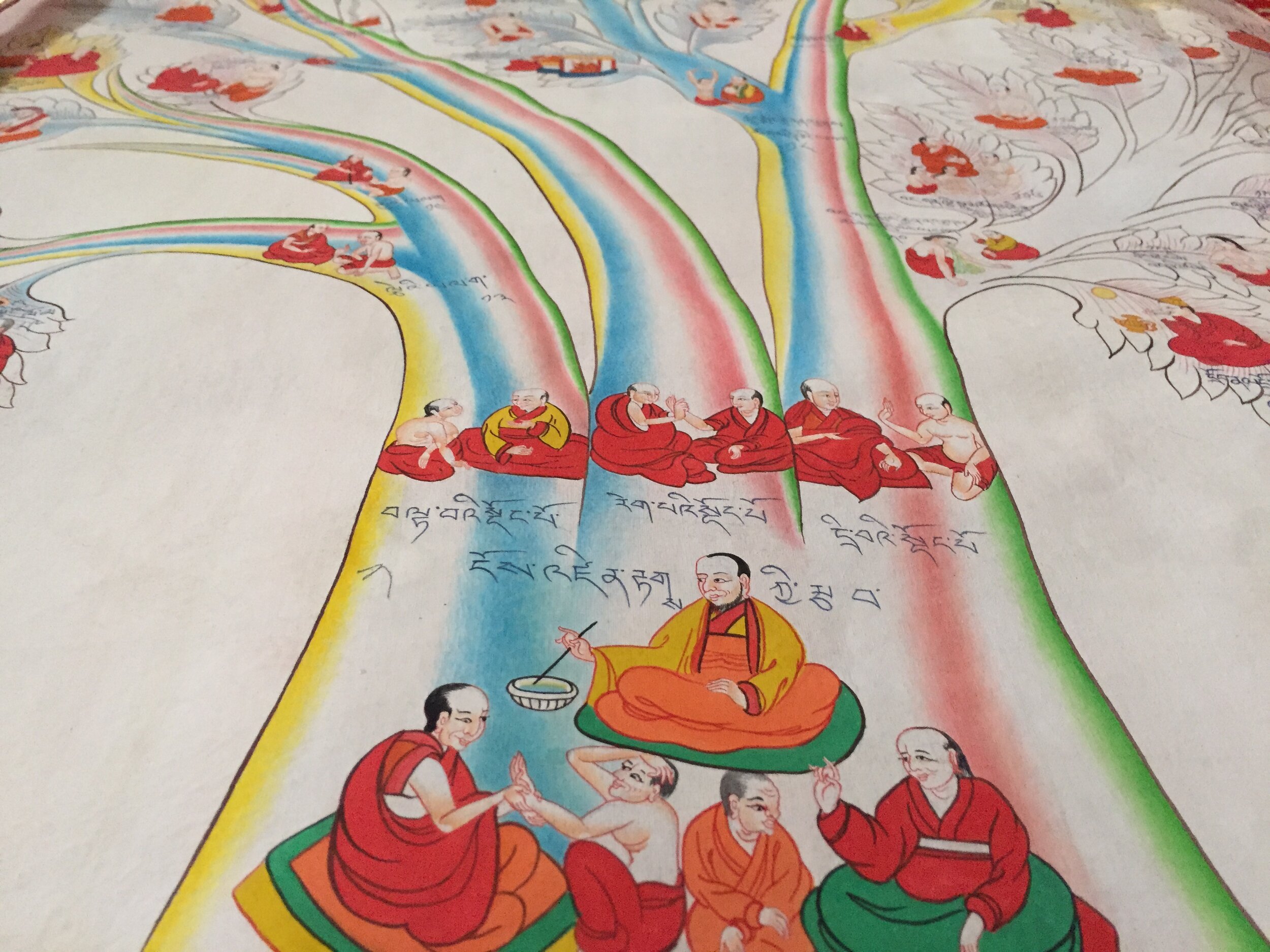

Tibetan Medicine is an ancient system of natural healing traditionally practised across the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau. With roots reaching back thousands of years, it is one of the oldest healing traditions in existence, with an unbroken transmission lineage stretching from deep history into today’s world.

In the Tibetan language, medicine is known as Sowa Rigpa, the “Science of Healing.” Sowa literally means “to heal,” though it also has connotations relating to more profound “nourishment.” Rigpa means “science,” referring to the five major sciences of antiquity: linguistics, logic, craftsmanship, medicine, and the inner science of Buddhadharma. According to Dr. Nida Chenagtsang, the most appropriate translation of Sowa Rigpa would be “The Science of Health and Happiness.”

Sowa Rigpa is a truly revolutionary form of medicine. In the imperial age of Tibet’s development (beginning around the 7th century), there was already a robust system of ancestral healing practice. But the Tibetan people were determined not to become rigid or fixed in their understanding of the phenomenal world. While many ancient healing systems were prone to dogmatic stagnation, rooted in the assertion that their own system was divinely inspired and uncontestable, Tibet found itself in a novel and powerful position.

Located at the very crossroads of many of the world’s most advanced ancient societies, it should come as no surprise that Tibetan Medicine embraced a potent cosmopolitan spirit during its formative years. There’s a wealth of accounts of famous foreign doctors making the long and dangerous journey to Tibet, where they would convene and collaborate with the greatest medical minds of their day. Despite their apparent isolation in the high Himalayas, early Tibetan scientists were some of the most cross-cultural and sophisticated minds in the ancient world.

Over time, the Tibetan approach to healing picked up steam and spread like wildfire across Asia. While we may call it “Tibetan Medicine” today, this same system of medicine is known and used in India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, Mongolia, Russia, China, and beyond. It is rightly seen as the ultimate syncretic blend of the greatest classical Eurasian healing disciplines. But despite its ready integration of foreign medical knowledge, Sowa Rigpa retained a distinctly Himalayan character, and was greatly influenced by both Buddhist and pre-Buddhist Tibetan spirituality. But the ultimate driving force behind Sowa Rigpa’s success, both in ancient and modern times, has always been its profound efficacy. In contrast to the exclusivist orientation of tantric Buddhism, Tibetan Medicine was always treated as an ecumenical science for all people, and numerous non-Buddhist cultures absorbed and adopted the practise of Sowa Rigpa based on its scientific merits alone. In particular, with privileged access to a most remarkable array of Himalayan, Indian, Chinese, and Middle Eastern medicinal plants and other substances, the Sowa Rigpa pharmacopoeia is one of the most sophisticated and vast in the world.

The Foundational Theories of Tibetan Medicine

In the 12th century, a physician from western Tibet named Yuthok Yönten Gönpo “the Younger” codified the now-famous Four Tantras (rGyud bZhi) of Tibetan Medicine. For almost a thousand years, these four seminal texts have formed the foundation of Tibetan Medical theory and practice. To this day, they are dutifully studied by Sowa Rigpa students all around the world.

According to the Four Tantras, disease arises due to an imbalance of the three nyépa, or three humours, which facilitate manifold physiological functions in our body. Humoural imbalance is itself rooted in the involvement of the three mental afflictions, which underwrite our entire universal experience of suffering. However, immediate factors such as diet, behaviour, season/time, and external provocation all contribute more tangible circumstances for disease to arise. When these factors negatively impact our physiology, balance gives way to imbalance, and disordered states arise.

With strong influence from Buddhist philosophy, Tibetan Medicine identifies that all compounded phenomena are temporally composed of the Five Elements. This includes our bodies, our psychological states, our diseases, and our treatments. When the patient, the illness, and the therapy are all clearly understood on this basis, we tap into a profound awareness of universal interdependence.

Interdependence, or tendrel, is a vital concept for understanding Sowa Rigpa. While much of modern complementary medicine is focused on the mind-body connection, Tibetan Medicine takes it a step further by fully embracing the union between sentient beings and our natural environment. An acute understanding of our energetic ecology makes Himalayan medicine an invaluable resource in our ongoing fight against climate destruction.

The Three Nyépa

Similar to the Ayurvedic and Greek traditions, Tibetan Medicine is a humoural medical system, identifying three (or four) principal physiological energies which facilitate all of our bodily functions, arising from the universal Five Elements. While the Tibetan humours are most closely related to the three doshas of Indian Ayurveda, intersectional influences from Hippocratic and Chinese medicine produced a highly nuanced and unique approach to elemental and humoural theory.

In short, the three humoural energies are known as rLung, Tripa, and Pekén. rLung, or wind, is the motility factor in the body, facilitating everything from peristalsis to neurological communication. This is roughly analogous to the Ayurvedic concept of vata, though the Tibetan manifestation has its own specific qualities unique to this highly advanced tradition. Tripa, or bile, is the heat function in the body, responsible for metabolism and maintenance of physical heat. Pekén, or phlegm, is the cool-natured manifestation of solidity and moisture in the body, producing the bulk of our physical form.

Each of these three humours are operative in every healthy body, with each of us expressing a basic typological predisposition to one, two, or all three forces. This is our biological constitution - it is established at birth, due to both genetic and gestational influences, and it informs our lifelong experience of health and disease. If we are mindful and diligent in protecting our state of humoural balance, then we can enjoy good health. But if they become imbalanced, then these three humours can also form the basis of disease, leading to unique manifestations of illness based on our own biological constitution.

Along with physiological components, rLung, Tripa, and Pekén are also closely connected to our psychology. While the humours themselves are formed from the Five Elements, imbalance within these energies are ultimately linked to the three poisons of aversion, desire, and ignorance. Within these fundamental mental afflictions we can find all manifestations of dualistic clinging, rejection, and delusion which precipitate as our basic negative emotions. In Tibetan psychiatry, these dynamics manifest as three principal forms of mental stress - the all-too familiar experiences of anxiety, anger, and depression. All of these negative mental states (and therefore imbalance of the humours themselves) are based in the single ultimate root of all suffering - unawareness or ma-rigpa. Due to our fundamental unawareness, we produce a basic rift from the ground of being, giving rise to apparent dualism and subject-object fixation. On this most essential level, we can see that a lack of depth understanding of our true quantum nature is the common root of all disease.

However, despite its profound philosophical context, Tibetan Medicine is not merely a system of energy healing, and it doesn’t fall into reductive dynamics of spiritual bypassing to insinuate that “it’s all in your head.” Medicine has always sat at an important intersection of philosophy and science, and Sowa Rigpa is among the most advanced systems to seamlessly integrate relative reality with an awareness of the absolute.

On a more immediate level, it’s seen that four conditioning factors ultimately cause disease to manifest in living beings: diet, behaviour, time/season, and external provocation. While nutrition can be a powerful kind of medicine, improper diet is also a leading cause of disease. Likewise, behaviour can be both a therapy and a condition for imbalance, making healthy diet & behaviour essential components of preventative medicine. Time and season relate to the natural cycles of the outer world, including both the perennial seasonal rotations and our 24-hour biological clock. Seasonal flus and allergies are two examples of how the outer cycles of time can impact our physiological equilibrium. The final factor, external provocation (gDon), is a fascinating and vast study of how ecological interdependence impacts personal health. Maintaining a positive and responsible relationship with the natural world is seen as a vital component of maintaining good health and avoiding disease. The understanding of external provocation also includes components like viral and bacterial infections, which are internal diseases caused by “external” organisms. Regardless of the cause, however, all experiences of disease are enacted through imbalance of the three humours.

Therapies in Sowa Rigpa

Tibetan Medicine utilizes four primary methods of treatment: diet, behaviour, herbal medicine, and external therapies. Among the foundational notions in Sowa Rigpa is the concept that every substance can be a medicine or a poison, depending on the method, amount, and circumstances of use. In particular, our diet and behaviour can be powerful forces both for supporting health and for instigating disease. As Hippocrates once said, “let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.”

All therapies in Sowa Rigpa are highly individualised - acknowledging that each of us have unique physiological needs and biological dynamics that influence our experience of health. There is no one size fits all approach to health, as any good traditional medicine practitioner can tell you. Typological classification and constitutional analysis help to determine exactly what method of treatment is most appropriate, acknowledging the underlying causes and conditions of disease instead of simply attacking the symptoms. Diet is approached seasonally and constitutionally, with a dynamic focus on personal typology, environmental circumstances, and the unique healing powers found in food. As with diet, behaviour is also approached individually, abandoning the notion that every one of us should engage in the same types of behaviour to maintain good health.

Herbal medicine is an immensely vast topic in Sowa Rigpa, especially in modern times. In truth, the term “herbal” medicine is a bit of a misnomer, as the traditional Tibetan pharmacopoeia goes beyond plant medicine to include minerals, sacred substances, animal products, and even precious gemstones in the preparation of medicine. In modern times, however, there is a remarkable effort to truly establish Sowa Rigpa in a global context, integrating the classical western herbal pharmacopoeia with Tibetan medical frameworks, and seeking more sustainable and ethical alternatives for rare, endangered, or otherwise unsustainable ingredients. In Europe, America, and beyond, modern Tibetan Medicine practitioners regularly work with a combination of ethically grown or wildcrafted herbs and traditional Himalayan formulae.

External therapies have long been an area of specialisation for Tibetan Medicine, particularly because fresh herbs and nutritional variety were not always accessible in the remote reaches of the Himalayas. Methods like moxibustion, acupuncture, massage, venesection, hot and cold compresses, and bath therapy were utilized by professionals and laymen in order to treat the body from the outside. Sowa Rigpa’s most famous hot compress therapy, hormé, has its roots in ancient Mongolia, when nomads would dip homemade felt in hot oil and apply it to particular points of the body as a soothing, warming therapy. Techniques like moxibustion and acupuncture are connected with the advancements of Chinese Medicine, but the Tibetan tradition uses a unique system of meridians and energy centres rooted in tantric Buddhist physiology and their own scientific research.

Along with these four treatment methods in Sowa Rigpa, the Tibetan Buddhist tradition offers a fifth category of spiritual healing, with various meditations, yoga techniques, and ritual practices designed to support good health and eradicate disease. On a most essential level, Buddhist practise works to quell the basic mental afflictions that underwrite our entire universal experience of suffering. But far from simple “stress-relief,” the tantric Buddhist tradition offers highly specific and technical methods for working with the body and mind, and the great yogis and yoginis of Tibet were responsible for a number of great medical advancements throughout Tibetan history, including novel external therapies, herbal formulae for novel diseases, and profound practises for reversing illness. The father of Tibetan Medicine, Yuthok Yönten Gönpo, himself authored a major cycle of spiritual practises connected to medicine, known as the Yuthok Nyingthig.